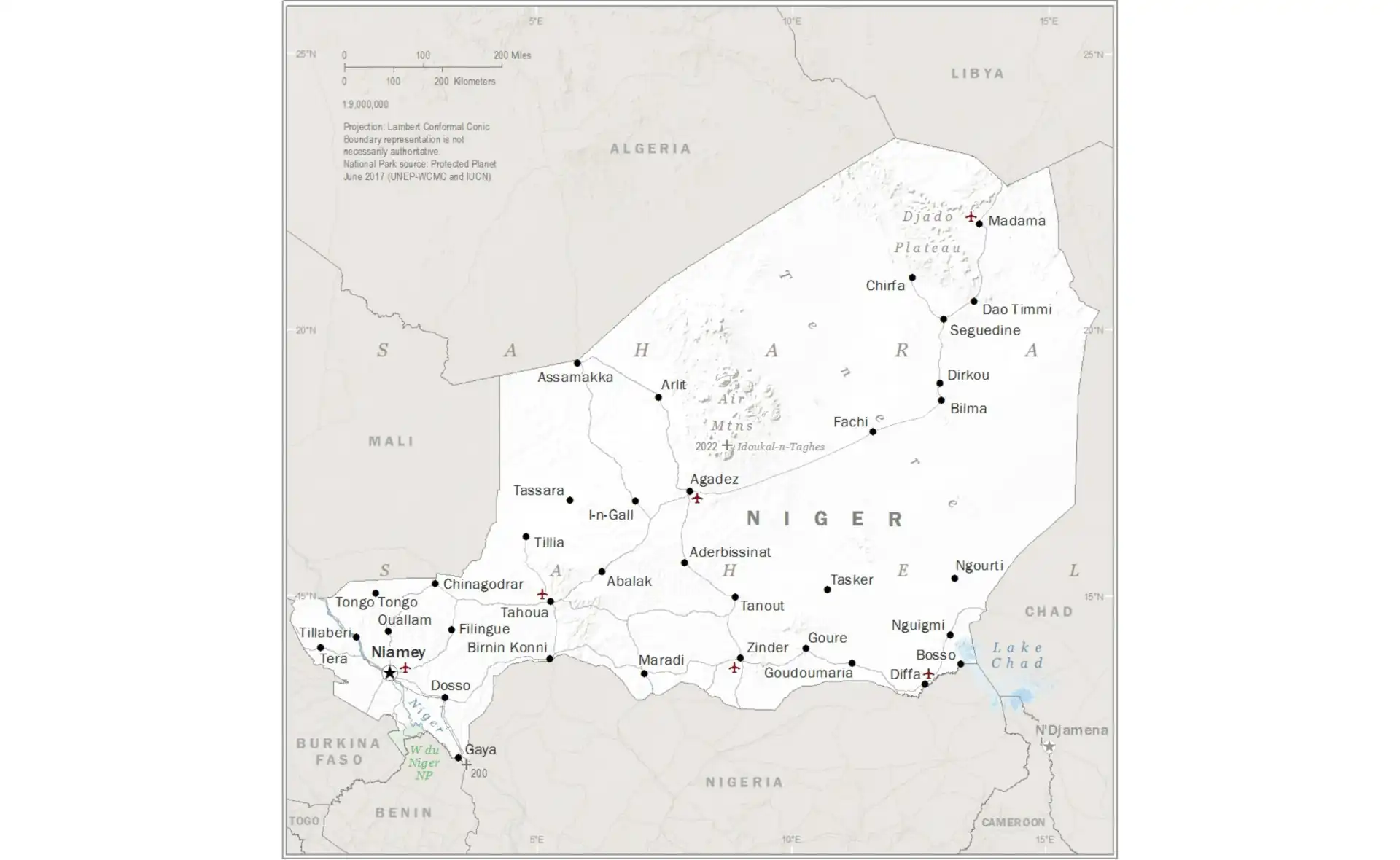

Niger: Gateway to the Sahara

The Republic of Niger, West Africa's largest country, spreads across 1.27 million square kilometers of dramatic landscapes ranging from the vast Sahara Desert to the life-giving Niger River. Named after the river that flows through its southwestern corner, Niger bridges Arab North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, creating a unique cultural crossroads. Despite facing significant development challenges, this landlocked nation holds strategic importance through its uranium reserves, ancient trading cities, and position along historic trans-Saharan routes that once connected Mediterranean civilizations with African kingdoms.

Geographic Extremes: From Desert to River

Niger's immense territory, roughly twice the size of France, encompasses some of Africa's most extreme environments. The country divides into distinct geographic zones that shape human settlement and economic activity. The northern two-thirds lie within the Sahara Desert, featuring vast expanses of sand dunes, rocky plateaus, and isolated mountain massifs. This seemingly barren landscape contains hidden treasures: ancient rock art, fossil beds, and mineral deposits that tell stories of dramatically different climates in the past when the Sahara was green.

The Air Mountains (Aïr Massif) rise dramatically from the desert floor in north-central Niger, creating an island of relative humidity in the arid expanse. These ancient volcanic mountains reach heights of over 2,000 meters, with Mount Bagzane at 2,022 meters marking Niger's highest point. The mountains support unique ecosystems and have served as refuges for both wildlife and human populations throughout history. Ancient trade routes wound through mountain passes, connecting sub-Saharan Africa with Mediterranean ports through chains of oases that still sustain life today.

Southern Niger presents a completely different landscape. Here, the Sahel zone transitions into savanna, supporting agriculture and the majority of the population. The Niger River enters the country from Mali, flowing for about 550 kilometers through Niger before continuing into Benin and Nigeria. This river creates a ribbon of life through otherwise arid lands, supporting fishing, agriculture, and transportation. The river valley's fertile soils contrast sharply with the sandy soils that dominate much of the country, making this region Niger's agricultural heartland.

Total Area

1.27 million km²

Desert Coverage

80% of territory

Population

25 million

Highest Peak

2,022 meters

Climate Challenges and Adaptations

Niger experiences one of the world's harshest climates, with extreme temperatures and minimal rainfall shaping every aspect of life. The Saharan north receives less than 150mm of rain annually, often going years without significant precipitation. Temperatures regularly exceed 45°C (113°F) during the hot season from March to June, while desert nights can be surprisingly cold. These extremes challenge human survival but have also fostered remarkable adaptations among Niger's peoples, from nomadic movement patterns to traditional architecture designed for thermal regulation.

Surviving the Sahara

Life in Niger's desert regions requires specialized knowledge and practices:

- Water Management - Traditional techniques for finding and conserving water, including knowledge of seasonal pools and underground sources

- Nomadic Pastoralism - Seasonal movements following rainfall and pasture availability, with herds of camels, goats, and cattle

- Desert Architecture - Mud-brick construction with thick walls for insulation and narrow streets for shade

- Traditional Navigation - Using stars, wind patterns, and landscape features to traverse vast desert expanses

- Social Networks - Complex systems of mutual aid and information sharing essential for survival in harsh conditions

The Sahel zone in southern Niger experiences a brief but intense rainy season from June to September, receiving 300-600mm of rainfall. This precipitation arrives in violent storms that can cause flash flooding and erosion, yet it represents the difference between life and death for farmers and pastoralists. The variability of rainfall from year to year creates constant uncertainty, with droughts occurring regularly and threatening food security. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, with rising temperatures and increasingly erratic rainfall patterns disrupting traditional agricultural and pastoral systems.

Ancient Civilizations and Trade Routes

Niger's strategic location made it a crucial link in trans-Saharan trade networks for over a millennium. The ancient city of Agadez, founded in the 11th century, became one of the most important caravan stops between North and West Africa. Merchants transported gold, salt, slaves, and ivory northward while bringing horses, weapons, and manufactured goods south. These trade routes created wealth and fostered cultural exchange, spreading Islam, architectural styles, and technologies across the Sahara.

Archaeological evidence reveals even older civilizations in Niger. The Kiffian and Tenerian cultures flourished in the "Green Sahara" period between 10,000 and 5,000 years ago when the region enjoyed a much wetter climate. Their remains, found at sites like Gobero, include sophisticated tools, pottery, and jewelry, demonstrating advanced societies adapted to lakeside environments. Rock art throughout the Air Mountains depicts elephants, giraffes, and cattle, testament to a dramatically different environment that supported diverse wildlife and human populations.

The Songhai Empire extended into western Niger during its height in the 15th and 16th centuries, bringing political organization and Islamic scholarship. The empire's collapse led to the rise of smaller kingdoms and city-states, including the Sultanate of Agadez and various Hausa states in the south. These polities maintained the trans-Saharan trade networks while developing distinctive cultural traditions. The arrival of European colonial powers in the late 19th century disrupted these ancient patterns, but their legacy continues to influence Niger's cultural landscape.

Cultural Diversity in a Harsh Land

Niger's population of approximately 25 million comprises numerous ethnic groups, each with distinct languages, customs, and economic strategies adapted to their environments. The Hausa people, representing about 55% of the population, dominate the southern agricultural zones. Their sophisticated farming techniques, including intercropping and soil conservation methods, allow productive agriculture in challenging conditions. Hausa culture, expressed through elaborate architecture, vibrant markets, and rich oral traditions, forms much of Niger's cultural mainstream.

The Tuareg: Desert Nomads

The Tuareg, about 10% of Niger's population, traditionally dominated the Saharan regions. Known as the "Blue People" for their indigo-dyed clothing, they developed a complex society based on nomadic pastoralism, trade, and raiding. Their ancient Tifinagh script, matrilineal social elements, and distinctive music have attracted international attention. Modern challenges include sedentarization pressures and political marginalization.

Fulani Herders

The Fulani (Peul) people, roughly 9% of the population, practice transhumant pastoralism throughout the Sahel zone. Their deep knowledge of cattle breeding and seasonal pastures makes them essential to Niger's livestock economy. Fulani social organization around cattle ownership and complex systems for accessing pasture and water demonstrate sophisticated environmental management.

Zarma-Songhai Heritage

The Zarma and Songhai peoples, together about 20% of the population, inhabit the Niger River valley. Their ancestors built the great Songhai Empire, and they maintain traditions of fishing, farming, and river trade. Their languages serve as lingua franca in western Niger, while their music and dance traditions influence national culture.

Islam unites about 99% of Niger's population, though practiced with considerable variation and often blended with pre-Islamic traditions. Sufi brotherhoods play important roles in education and social organization, while traditional healers and spirit possession cults continue alongside Islamic practice. This religious synthesis creates a tolerant religious environment where extreme interpretations historically found little support, though recent regional instability has introduced new tensions.

Uranium: Blessing and Curse

Niger possesses Africa's highest-grade uranium ore deposits, making it the world's fifth-largest uranium producer. Mining began in 1971 with French company Areva (now Orano) developing mines around Arlit in the northern desert. These operations transformed Niger's economy and international relations, providing the majority of government revenues for decades. The uranium powered France's nuclear energy program while offering Niger a source of income in an otherwise resource-poor economy.

The Uranium Economy

Uranium mining profoundly impacts Niger's development:

- Economic Dependence - Uranium exports account for 70% of export earnings but employ relatively few people directly

- Environmental Concerns - Mining creates radioactive waste and consumes scarce water resources in desert regions

- Geopolitical Importance - Strategic uranium reserves attract international attention and influence foreign relations

- Local Impacts - Mining towns like Arlit experience boom-bust cycles tied to global uranium prices

- Future Prospects - New mines and international competition reshape the industry's role in Niger's economy

The uranium sector illustrates broader challenges in Niger's development model. Despite decades of extraction, the country remains among the world's poorest, ranking last on the UN Human Development Index. Critics argue that unfavorable contracts, corruption, and lack of value addition mean Niger captures too little benefit from its resources. Environmental and health impacts on mining communities raise additional concerns. Recent governments have attempted to renegotiate contracts and diversify the economy, but uranium remains central to state finances and international relations.

Agricultural Struggles and Innovations

Agriculture employs about 80% of Niger's population but faces enormous challenges from climate, soil quality, and population pressure. The short rainy season limits crop options to drought-resistant varieties of millet, sorghum, cowpeas, and groundnuts. Traditional farming techniques, including leaving fields fallow and incorporating livestock manure, maintained soil fertility for centuries. However, population growth has shortened fallow periods and expanded cultivation onto marginal lands, leading to declining yields and environmental degradation.

Innovative approaches show promise for improving agricultural productivity while protecting the environment. Farmer-managed natural regeneration, a technique allowing native trees to regrow in fields, has restored tree cover on over 5 million hectares. These trees improve soil fertility, provide fodder and fuel, and increase crop yields. Water harvesting techniques, including stone lines and half-moon catchments, concentrate scarce rainfall and reduce erosion. Small-scale irrigation along the Niger River and seasonal ponds enables dry season gardening, providing vegetables and income.

Pastoralism remains crucial for Niger's economy and food security, with livestock representing the second-largest export after uranium. Traditional pastoral systems, based on mobility and complex resource-sharing arrangements, efficiently utilize variable rainfall and pasture resources. However, expanding farmland, international borders restricting movement, and climate change pressure these systems. Conflicts between farmers and herders over resources increasingly challenge rural stability. Supporting sustainable intensification of both farming and herding while managing competition for resources represents a critical development challenge.

Population Growth and Youth Challenges

Niger has the world's highest fertility rate, with women averaging seven children. This creates the world's youngest population structure, with a median age of just 15 years. While a young population could provide demographic dividends through a large workforce, Niger struggles to create opportunities for its youth. The population doubles every 18 years, straining already limited resources and services. Traditional values favoring large families clash with economic realities, creating tensions between generations and genders.

Education faces enormous challenges in this context. Despite constitutional guarantees of free education, only about 60% of children complete primary school, with girls particularly disadvantaged. Schools often lack basic infrastructure, qualified teachers, and materials. Many children, especially in rural areas, balance school with farming or herding responsibilities. Higher education remains limited, with few university places relative to demand. This educational deficit limits economic transformation possibilities and traps many in subsistence activities.

Youth unemployment and underemployment create social and political pressures. Most young people work in informal agriculture or petty trade with minimal income. Urban areas cannot absorb rural migrants, leading to growing slums around cities like Niamey and Maradi. Some youth turn to migration, attempting dangerous journeys to North Africa and Europe. Others become vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups operating in the region. Addressing youth aspirations while creating sustainable livelihoods represents Niger's greatest long-term challenge.

Political Evolution and Democracy

Niger's political history since independence in 1960 reflects broader West African patterns of military coups, single-party rule, and democratic transitions. The first president, Hamani Diori, maintained close ties with France while attempting modernization. His overthrow in 1974 initiated a pattern of military interventions justified by corruption and economic mismanagement. Lieutenant Colonel Seyni Kountché ruled until 1987, implementing austere policies while benefiting from uranium boom revenues.

The 1990s brought democratization following national conferences that swept francophone Africa. Multi-party elections in 1993 produced Niger's first democratic transition, but political instability led to another military coup in 1996. A period of alternating military and civilian rule followed until 1999, when another coup brought Mamadou Tandja to power. Initially respected for restoring stability, Tandja's attempt to extend his presidency beyond constitutional limits triggered a 2010 military coup that led to a successful democratic transition.

Recent years have seen democratic progress despite security challenges. Presidents Mahamadou Issoufou (2011-2021) and Mohamed Bazoum (elected 2021) maintained constitutional order while facing jihadist insurgencies and economic pressures. However, a military coup in July 2023 ended this democratic period, with the military citing security failures and foreign interference. This latest intervention reflects regional trends of democratic backsliding and military resurgence, raising questions about Niger's political future and international relationships.

Security Challenges in the Sahel

Niger sits at the epicenter of the Sahel security crisis, facing threats from multiple jihadist groups operating across porous borders. Boko Haram attacks from Nigeria affect the southeastern Diffa region, displacing hundreds of thousands. In the west, groups affiliated with Islamic State and al-Qaeda operate from bases in Mali and Burkina Faso, attacking military posts and civilians. The vast, sparsely populated terrain makes securing borders nearly impossible, while poverty and marginalization create recruitment opportunities for armed groups.

International military presence has been significant, with France maintaining Operation Barkhane forces and the United States operating drone bases. The UN peacekeeping mission in Mali affects Niger's security, while the G5 Sahel joint force attempts regional coordination. However, these interventions face criticism for failing to improve security while potentially exacerbating local tensions. The 2023 coup partly reflected frustration with continued insecurity despite foreign military presence, leading to demands for French withdrawal and questions about future security partnerships.

Beyond jihadist threats, Niger faces interconnected security challenges. Banditry and kidnapping plague rural areas, while arms and drug trafficking through the Sahara fund criminal networks. Climate-related resource conflicts between farmers and herders escalate into communal violence. Artisanal gold mining attracts fortune seekers but also criminal elements. These overlapping insecurities undermine development efforts and state authority, particularly in peripheral regions where government presence was always limited.

Urban Growth and Niamey

Niamey, Niger's capital and largest city, has grown from a small colonial outpost to a metropolis of over 1.3 million people. Situated on the Niger River's banks, the city spreads across both sides connected by the Kennedy Bridge. Modern Niamey presents stark contrasts: government buildings and hotels in the Plateau district overlook sprawling informal settlements lacking basic services. The Grand Marché bustles with traders from across West Africa, while new neighborhoods struggle with water and electricity access.

Urban growth strains infrastructure designed for a much smaller population. Traffic congestion worsens as motorcycle taxis weave between cars on potholed roads. Waste management cannot keep pace with population growth, leading to pollution and health hazards. The Niger River, Niamey's lifeline, faces pollution from urban runoff and untreated sewage. During the rainy season, flooding threatens riverside communities, while water shortages paradoxically affect many neighborhoods year-round.

Despite challenges, Niamey remains Niger's economic and cultural center. The University of Niamey, established in 1971, provides higher education opportunities despite overcrowding. Cultural institutions like the National Museum preserve and showcase Niger's heritage. The city's music scene blends traditional and modern styles, while restaurants serve cuisines reflecting Niger's diversity. As rural-urban migration continues, Niamey's ability to provide opportunities while managing growth will significantly impact national development.

Women's Roles and Gender Issues

Nigerien women face some of the world's most challenging conditions, with the country ranking last on the UN Gender Inequality Index. Early marriage remains common, with 76% of girls married before 18 and 28% before 15. These practices limit educational opportunities and perpetuate cycles of poverty and high fertility. Maternal mortality rates rank among the world's highest due to limited healthcare access and frequent pregnancies. Despite constitutional equality guarantees, customary and Islamic law often restricts women's rights in practice.

However, women play crucial economic roles often unrecognized in official statistics. They dominate small-scale trade, manage household food security, and increasingly engage in agriculture as male migration increases. Women's groups and cooperatives provide mutual support and economic opportunities, from vegetable gardening to crafts production. In pastoral communities, women manage milk production and marketing, controlling important income sources. These economic contributions challenge traditional gender narratives while providing pathways for empowerment.

Recent years have seen growing activism for women's rights despite conservative resistance. Female literacy campaigns, though starting from a low base of under 20% literacy, show progress. Women's political participation slowly increases, with quotas ensuring minimal representation in elected bodies. Family planning programs, though controversial, gain acceptance as economic pressures mount. International development programs increasingly recognize that improving women's status is essential for broader development goals, though cultural change remains slow.

Environmental Degradation and Conservation

Niger faces severe environmental challenges threatening its long-term sustainability. Desertification advances as the Sahara expands southward, driven by climate change and human activities. Overgrazing, deforestation for fuel and farmland, and shortened fallow periods degrade soil quality. Wind erosion during the dry season creates dust storms that strip topsoil and reduce visibility. Water resources face increasing pressure from population growth, with groundwater levels declining and seasonal rivers drying earlier.

Conservation efforts show both challenges and possibilities. The Air and Ténéré Natural Reserves, designated as World Heritage sites, protect unique Saharan ecosystems and endangered species like the addax antelope and dama gazelle. However, insecurity limits conservation activities while poaching threatens remaining wildlife. Community-based natural resource management programs show success where local people benefit from conservation. The Great Green Wall initiative aims to restore vegetation across the Sahel, though implementation faces funding and coordination challenges.

Perhaps most encouraging is the farmer-managed natural regeneration movement, demonstrating that environmental restoration can accompany agricultural development. By protecting naturally regenerating trees and shrubs in their fields, farmers have increased tree cover, improved soil fertility, and diversified income sources. This low-cost, locally driven approach offers lessons for sustainable development in drylands worldwide. However, scaling such successes requires supportive policies, secure land tenure, and long-term commitment amid pressing immediate needs.

International Relations and Regional Integration

Niger's foreign policy balances relationships with multiple partners while navigating regional instabilities. France maintained dominant influence since independence through military agreements, development aid, and uranium contracts. However, anti-French sentiment has grown, particularly among youth who view France as exploitative and ineffective against security threats. The 2023 coup accelerated this shift, with military leaders demanding French military withdrawal and reviewing uranium agreements.

Regional relationships through ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) and the African Union provide frameworks for cooperation but also tensions. Niger participates in regional integration efforts including common external tariffs and free movement protocols. However, the 2023 coup triggered ECOWAS sanctions and border closures, highlighting regional divisions about democratic norms versus sovereignty. The G5 Sahel initiative for security cooperation faces challenges as member states pursue different strategies against shared threats.

Newer partnerships diversify Niger's international relations. China invests in infrastructure and oil exploration, offering alternatives to Western partners. Turkey, Russia, and Gulf states increase presence through aid, investment, and security cooperation. The United States maintains significant military presence through drone bases, though future cooperation remains uncertain. Managing these diverse relationships while maintaining sovereignty and securing development resources challenges Niger's diplomatic capacity.

Future Prospects and Challenges

Niger's future trajectory depends on addressing interconnected challenges while building on cultural resilience and natural resources. The demographic explosion continues, with the population projected to reach 65 million by 2050 if current trends persist. Creating productive employment for millions of youth requires economic transformation beyond current capabilities. Climate change threatens traditional livelihoods while new technologies offer possibilities for leapfrogging development stages. Political stability remains precarious with military rule raising questions about democratic governance and international partnerships.

Opportunities exist despite daunting challenges. Niger's strategic location could make it a renewable energy powerhouse, with vast solar potential and growing regional energy demand. Digital technologies enable new services and connections, with mobile phone penetration growing rapidly. Young people's entrepreneurial energy, if channeled productively, could drive innovation. Cultural diversity and resilience provide social capital for development. Regional integration, despite current tensions, offers markets and cooperation frameworks essential for landlocked Niger.

Ultimately, Niger's development requires balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability. Addressing security threats while maintaining human rights, managing population growth while respecting cultural values, exploiting natural resources while protecting the environment, and engaging international partners while maintaining sovereignty all require careful navigation. The Nigerien people's remarkable adaptations to one of Earth's most challenging environments demonstrate resilience that, combined with appropriate support and policies, could enable sustainable development. As the Sahel faces unprecedented pressures from climate change, population growth, and security threats, Niger's success or failure will significantly impact regional and global stability.