Lesotho: Kingdom in the Sky

The Kingdom of Lesotho, aptly nicknamed the "Kingdom in the Sky," stands as one of only three countries in the world completely surrounded by another country—in this case, South Africa. With its entire territory sitting above 1,000 meters and the lowest point at 1,400 meters, Lesotho claims the title of the world's highest country. This mountain kingdom preserves unique Basotho culture, provides crucial water resources to southern Africa, and offers dramatic landscapes that include the highest peaks south of Kilimanjaro.

Geography: A Nation Above the Clouds

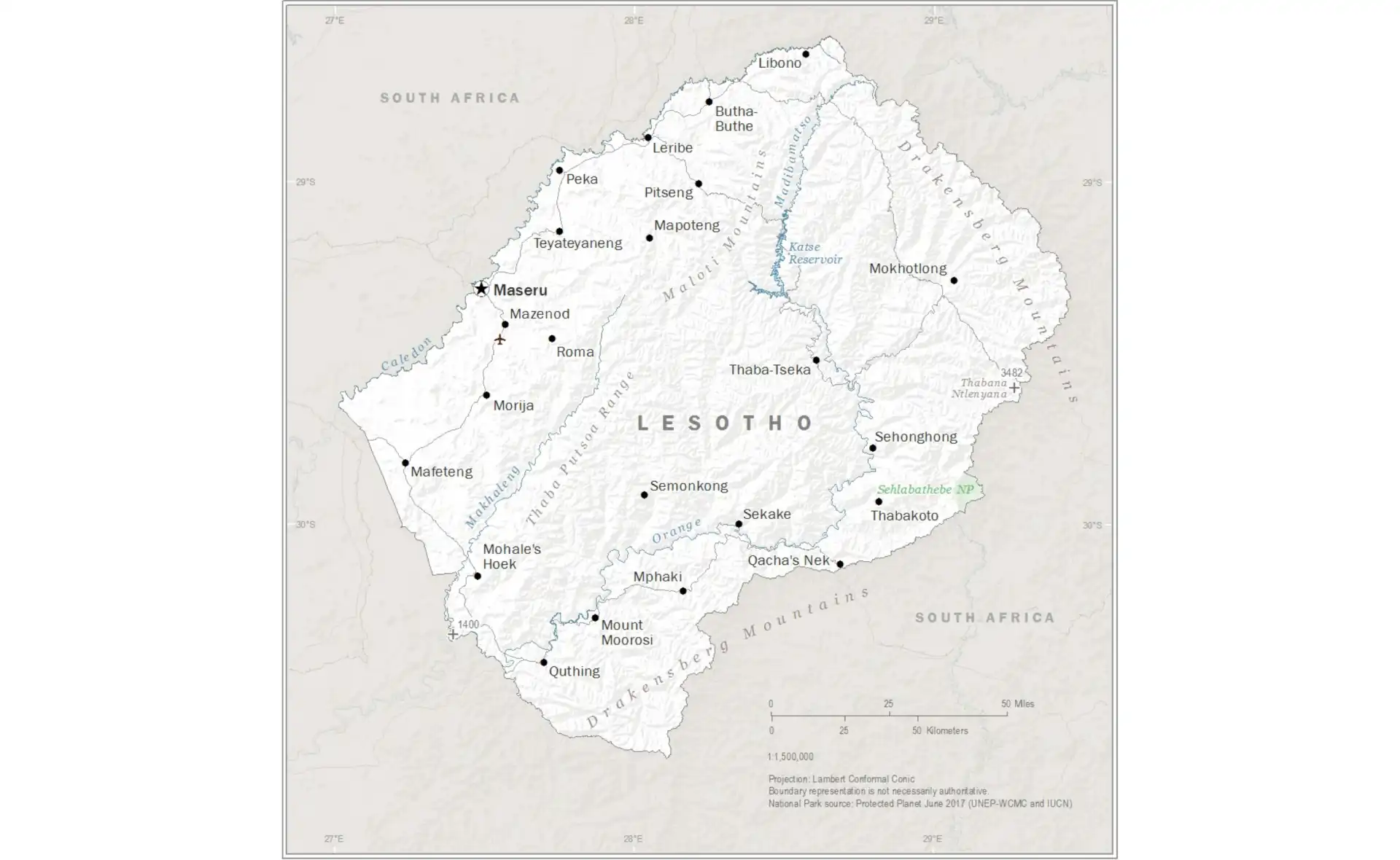

Lesotho's extraordinary geography defines every aspect of national life. Covering 30,355 square kilometers—roughly the size of Belgium—the country divides into distinct highland and lowland regions, though even the "lowlands" sit higher than most African mountains. The western lowlands, comprising about one-third of the territory, range from 1,400 to 1,800 meters elevation and contain most of the population and agricultural land. Here, the capital Maseru and other major towns cluster along the Caledon River valley, which forms much of the western border with South Africa.

The central and eastern regions rise dramatically into the Maloti Mountains, part of the greater Drakensberg range. These highlands cover two-thirds of the country and include southern Africa's highest peak, Thabana Ntlenyana, at 3,482 meters. The mountain landscape features deep valleys, high plateaus, and spectacular basalt cliffs formed by ancient volcanic activity. Alpine vegetation dominates above 2,500 meters, creating landscapes more reminiscent of the Himalayas than typical African terrain. Snow covers the highest peaks in winter, enabling Lesotho to offer Africa's only skiing opportunities.

Rivers originating in Lesotho's mountains play crucial regional roles. The Orange River (known locally as the Senqu) begins here, flowing westward to the Atlantic Ocean through South Africa and forming the border with Namibia. The Tugela River flows eastward to the Indian Ocean, creating spectacular waterfalls including the Tugela Falls, arguably Africa's highest. These water resources make Lesotho southern Africa's water tower, with the massive Lesotho Highlands Water Project transferring water to South Africa's industrial heartland through a series of dams and tunnels.

Total Area

30,355 km²

Lowest Point

1,400 meters

Highest Peak

3,482 meters

Population

2.3 million

The Mountain Kingdom's Unique Climate

Lesotho experiences a temperate climate with significant variations based on elevation. The country enjoys over 300 days of sunshine annually, earning it another nickname: "Kingdom of Light." However, temperatures vary dramatically with altitude and season. Summer (October to April) brings warm days and afternoon thunderstorms, with lowland temperatures reaching 30°C while highland areas remain cool. Winter (May to September) transforms the mountains into a frozen wonderland, with temperatures dropping below -20°C at high elevations and snow blanketing peaks and valleys.

Life in the Highlands

The harsh mountain environment shapes unique adaptations:

- Traditional Architecture - Round stone huts (rondavels) with thatched roofs withstand mountain winds and provide insulation

- Basotho Ponies - Sure-footed horses adapted to steep terrain serve as primary transportation in roadless areas

- Mohair Production - Angora goats thrive in the cool, dry climate, making Lesotho a major mohair producer

- Alpine Flora - Unique plants including the spiral aloe (Lesotho's national plant) adapted to extreme conditions

- Traditional Blankets - Colorful Basotho blankets provide warmth and cultural identity in the cold climate

Rainfall patterns create distinct ecological zones. The lowlands receive 600-800mm annually, mostly during summer thunderstorms. Mountain areas can receive over 1,200mm, with snow contributing significant moisture. However, the steep terrain and thin soils make much of this water quickly run off, creating erosion challenges while feeding the rivers that sustain the region. Climate change increasingly affects these patterns, with more intense storms and prolonged droughts threatening traditional agricultural systems and water security.

Historical Foundations

The Basotho nation emerged from the chaos of the early 19th century Mfecane/Difaqane, a period of warfare and displacement across southern Africa. King Moshoeshoe I, born around 1786, demonstrated exceptional leadership by gathering scattered clans and refugees fleeing Zulu expansion and other conflicts. In 1824, he established his stronghold at Thaba Bosiu, a flat-topped mountain that proved impregnable to attacks. From this natural fortress, Moshoeshoe built a nation through diplomacy, strategic marriages, and defensive warfare rather than conquest.

Moshoeshoe's wisdom extended to managing European encroachment. As Boer trekkers pressed into Basotho territory from the 1830s, leading to a series of wars over land, he sought British protection. In 1868, Basutoland became a British protectorate, preserving Basotho independence when neighboring African kingdoms fell to colonial conquest. This decision, though limiting sovereignty, prevented absorption into the expanding Boer republics and later the Union of South Africa, ultimately enabling Lesotho's existence as an independent nation.

The colonial period saw limited development but preserved Basotho social structures and chiefly authority. The British ruled indirectly through traditional leaders, allowing customary law to govern most aspects of daily life. Christian missionaries, invited by Moshoeshoe, established schools and churches, creating high literacy rates unusual in colonial Africa. The 1950s brought political awakening with the formation of modern political parties. Independence came peacefully on October 4, 1966, with King Moshoeshoe II as constitutional monarch, making Lesotho one of the few African states to maintain pre-colonial political continuity.

Basotho Culture and Identity

Basotho identity remains remarkably cohesive, with about 99% of the population sharing common ancestry, language (Sesotho), and cultural practices. This homogeneity, unusual in Africa, stems from Moshoeshoe I's nation-building that incorporated diverse groups into a unified culture. The Sesotho language, one of South Africa's official languages, serves as a cultural bridge with millions of Sesotho speakers across the border. Traditional praise poetry (lithoko) preserves history and values, performed at ceremonies and teaching cultural ideals of peace, justice, and community.

Traditional Dress

The iconic Basotho blanket evolved from 19th-century trade but became central to cultural identity. Worn as everyday clothing and ceremonial regalia, different patterns mark life stages and occasions. The conical straw hat (mokorotlo) appearing on the national flag represents Basotho identity. Traditional dress adapts to modern life while maintaining cultural significance.

Initiation Schools

Lebollo initiation schools for boys and girls transmit cultural knowledge and mark the transition to adulthood. Boys spend months in mountain lodges learning history, customs, and responsibilities. Despite modernization pressures, these schools remain important, with even urban youth returning for initiation during school holidays.

Music and Dance

Traditional music features call-and-response singing, with instruments like the lekolulo (flute) and setolo-tolo (stringed instrument). The mokhibo and mohobelo dances express joy and warrior traditions respectively. Contemporary artists blend traditional sounds with modern genres, creating unique Sesotho jazz and hip-hop scenes.

Social organization centers on extended families and villages led by chiefs who allocate land and resolve disputes. The pitso (public assembly) allows community participation in decision-making, embodying democratic traditions predating modern politics. Women traditionally hold significant authority within families and as custodians of culture, though patriarchal elements limit public roles. The practice of bohali (bridewealth) continues but adapts to modern economic realities, with negotiations reflecting changing gender relations and economic pressures.

Water: Lesotho's White Gold

Lesotho's mountain watersheds generate enormous water resources relative to its size, earning water the nickname "white gold." The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), one of Africa's largest infrastructure projects, exemplifies water's economic importance. This multi-phase project diverts water from the Senqu/Orange River system through a series of dams and tunnels to South Africa's Gauteng Province, generating hydroelectric power for Lesotho while earning crucial revenue. The project demonstrates both opportunities and challenges of resource exploitation in developing nations.

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project

This engineering marvel transforms Lesotho's water abundance into economic opportunity:

- Katse Dam - Africa's second-largest curved concrete dam, creating a reservoir in the Maloti Mountains

- Mohale Dam - Connected to Katse via a 32km tunnel through the mountains

- Revenue Generation - Water royalties provide significant government income, funding development projects

- Hydroelectric Power - The Muela plant generates 72MW, moving Lesotho toward energy self-sufficiency

- Environmental Impact - Displaced communities and altered ecosystems raise sustainability questions

Beyond the LHWP, water resources support diverse uses. Mountain streams provide domestic water for rural communities, though access remains challenging in remote areas. Wetlands, including the Ramsar-listed Lets'eng-la-Letsie, support biodiversity and pastoral livelihoods. However, overgrazing and climate change threaten these ecosystems. Traditional water management practices, including seasonal grazing patterns and communal spring protection, offer lessons for sustainable resource use but face pressure from population growth and modernization.

Economic Challenges and Opportunities

Lesotho's economy faces structural challenges from geographic isolation, limited arable land, and dependence on South Africa. Agriculture employs about 60% of the population but contributes only 7% to GDP, reflecting low productivity on marginal mountain soils. Subsistence farming of maize, sorghum, and wheat barely meets household needs, with frequent droughts causing food insecurity. Livestock, particularly sheep for wool and mohair production, provides cash income but overgrazing degrades rangelands. Agricultural modernization efforts face terrain constraints and climate variability.

Manufacturing developed through preferential trade agreements, particularly textile production for US markets under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Taiwanese and Chinese-owned factories employ about 40,000 workers, mostly women, producing garments for major brands. However, this sector remains vulnerable to global competition and trade policy changes. Mining contributes through diamond extraction at high-altitude mines like Lets'eng, which produces large, high-value stones. Small-scale sandstone quarrying provides building materials but often operates informally with environmental costs.

The service sector grows slowly, constrained by small domestic markets. Tourism offers potential given spectacular mountain scenery, but poor infrastructure limits access. Remittances from Basotho working in South African mines historically sustained rural households, but mine employment has declined drastically. Youth unemployment exceeds 30%, driving urban migration and social tensions. Economic diversification remains elusive, with geographic constraints and South African economic dominance limiting options. Government employment provides significant formal sector jobs but strains public finances.

Political Evolution and Governance

Lesotho's post-independence politics reflects tensions between traditional authority and modern democratic institutions. The dual system recognizes both elected government and traditional chiefs, creating complex governance structures. Principal chiefs control land allocation and customary law in rural areas, while elected councils manage development. This duality sometimes creates conflicts but also provides checks and balances. The monarchy's role evolved from executive to largely ceremonial, though royal influence remains significant in national identity.

Political instability marked much of Lesotho's independence, with military coups, election disputes, and external interventions. The 1998 post-election violence that prompted South African military intervention highlighted democratic fragility. Constitutional reforms introducing proportional representation aimed to increase inclusivity. Recent years show greater stability, with peaceful transfers of power, though coalition governments prove fractious. The three main parties—All Basotho Convention, Democratic Congress, and Basotho National Party—reflect personal rivalries more than ideological differences.

Governance challenges include weak institutions, corruption, and limited state capacity in remote areas. Chiefs' control over land allocation creates opportunities for abuse while providing traditional dispute resolution. The judiciary maintains relative independence but faces case backlogs and limited reach. Civil society organizations advocate for democracy and human rights but operate in constrained space. Youth increasingly demand accountable governance and economic opportunities, using social media to organize despite limited internet penetration. Building effective governance while respecting traditional authority remains an ongoing challenge.

Education and Human Development

Lesotho achieved remarkable education progress, with one of Africa's highest literacy rates at about 80%. Free primary education, introduced in 2000, increased enrollment dramatically. Mission schools established by 19th-century missionaries created an education tradition valuing learning. However, quality challenges persist with overcrowded classrooms, undertrained teachers, and limited materials. Mountain schools face particular difficulties with teacher retention and student attendance during harsh weather. Secondary enrollment drops sharply as fees and opportunity costs exclude poor students.

The National University of Lesotho, established in 1975, provides higher education but faces funding constraints and brain drain. Many graduates seek opportunities abroad, particularly in South Africa, depleting human capital. Technical and vocational training remains underdeveloped despite unemployment challenges. Traditional knowledge transmission through initiation schools operates parallel to formal education, sometimes creating conflicts over time and values. Efforts to integrate cultural education into curricula face resource and ideological challenges.

Health indicators show mixed progress. Life expectancy plummeted due to HIV/AIDS, which affects about 25% of adults—the world's second-highest prevalence. Aggressive treatment programs show success, with declining new infections and increased treatment coverage. However, tuberculosis co-infection and limited healthcare access in mountains create ongoing challenges. Maternal and child health improved through focused programs, but malnutrition affects many children. Traditional medicine remains important, particularly in remote areas where modern healthcare is hours or days away by horseback.

Environmental Conservation and Challenges

Lesotho's mountain ecosystems face severe degradation from overgrazing, soil erosion, and climate change. Centuries of livestock grazing transformed grasslands, reducing biodiversity and soil fertility. Dramatic gully erosion scars landscapes, with some areas losing over 40 tons of soil per hectare annually. This erosion reduces agricultural productivity, silts dams, and threatens water resources. Traditional grazing management systems broke down under population pressure and changed economic conditions, while unclear land tenure complicates conservation efforts.

Protected areas cover only about 0.5% of the territory, far below international targets. Sehlabathebe National Park, Lesotho's only national park, protects high-altitude ecosystems and forms part of the Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation Area with South Africa. However, limited resources constrain management effectiveness. Community-based natural resource management programs show promise, linking conservation with livelihood benefits. Wetland protection gains attention given their role in water provision, but implementation remains weak.

Climate change impacts accelerate environmental challenges. Temperature increases exceed global averages, altering precipitation patterns and extending droughts. Snow cover declines affect water resources and the small ski industry. Extreme weather events increase, with devastating floods alternating with severe droughts. Adaptation efforts include conservation agriculture and rangeland rehabilitation, but scale remains limited. Renewable energy potential from hydro, solar, and wind could reduce dependence on imported electricity while supporting climate goals. Environmental sustainability requires balancing immediate livelihood needs with long-term resource protection.

Urban Development and Rural Realities

Maseru, home to about 330,000 people, dominates urban Lesotho as the capital and only major city. Straddling the Caledon River border with South Africa, Maseru grew from a small police camp to a sprawling city struggling with rapid urbanization. Colonial-era buildings mix with modern developments, while informal settlements expand on the periphery. The city concentrates government offices, businesses, and services, creating a primate city pattern that limits regional development. Infrastructure struggles to keep pace, with water shortages, power outages, and traffic congestion daily challenges.

Secondary towns like Teyateyaneng, Mafeteng, and Mohale's Hoek serve as regional centers but remain small with limited economic opportunities. These towns link rural areas to national systems but lack investment for significant development. Border towns benefit from cross-border trade, both formal and informal, with South Africa. The textile industry concentrates in Maseru and Maputsoe, creating employment clusters but limited broader development. Urban planning faces challenges from rapid growth, limited resources, and unclear land tenure in peri-urban areas.

Rural areas, home to 70% of Basotho, face isolation and limited services. Mountain villages accessible only by footpath or horseback remain cut off during winter storms. Basic services like electricity, piped water, and healthcare concentrate in lowlands, leaving highlanders marginalized. Mobile phone coverage improves connectivity but cannot replace physical infrastructure. Rural-urban migration accelerates as youth seek education and employment, leaving aging populations to maintain agricultural systems. Balancing urban growth with rural development remains a critical challenge for equitable progress.

International Relations in a Surrounded State

Lesotho's complete encirclement by South Africa creates unique foreign policy constraints and opportunities. Economic integration through the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) provides significant revenue but limits policy autonomy. The Common Monetary Area ties the loti to the rand, ensuring stability but preventing independent monetary policy. Labor migration agreements historically provided employment for Basotho miners, though numbers declined from over 100,000 to fewer than 30,000. This geographic reality makes good relations with South Africa essential for survival.

Regional integration through the Southern African Development Community (SADC) offers broader connections, but practical benefits remain limited given geographic isolation. Lesotho contributes to regional peacekeeping despite small military capacity. Relations with other African states focus on solidarity and shared development challenges. The African Union provides diplomatic support, particularly on issues like climate change adaptation where mountain states share vulnerabilities. However, landlocked status and South African dominance constrain independent foreign policy.

International development partnerships provide crucial support, with donors funding about 20% of the national budget. Traditional partners include the United States, European Union, and United Nations agencies. China increases presence through infrastructure projects and business investments, offering alternatives to Western aid. Climate finance gains importance given Lesotho's vulnerability. Diaspora communities, particularly in South Africa and the United Kingdom, maintain connections through remittances and knowledge transfer. Balancing sovereignty with dependence challenges this small mountain kingdom's international engagement.

Future Prospects and Challenges

Lesotho's future depends on navigating geographic constraints while leveraging unique assets. The young population—with median age around 24—presents both opportunity and challenge. Harnessing youth energy requires massive job creation beyond traditional sectors. Digital technology offers possibilities for overcoming physical isolation, with growing mobile penetration enabling financial inclusion and service delivery. However, creating productive employment for educated youth remains elusive. Without opportunities, social tensions and emigration will accelerate.

Economic transformation requires moving beyond dependence on water exports, textiles, and remittances. Tourism potential remains underdeveloped despite spectacular scenery and unique culture. Improving infrastructure, particularly all-weather roads to mountain areas, could unlock economic opportunities while reducing isolation. Value addition to agricultural products, particularly wool and mohair, could increase incomes. The cannabis industry, recently legalized for medical exports, offers new possibilities but requires careful management. Green economy initiatives leveraging Lesotho's renewable energy potential align with global climate goals.

Climate change adaptation represents an existential challenge requiring international support. Building resilience in agricultural systems, protecting water resources, and preparing for extreme weather demands resources beyond national capacity. Strengthening traditional coping mechanisms while adopting new technologies offers pathways forward. Ultimately, Lesotho must balance preserving unique Basotho culture with necessary modernization. The kingdom's survival through centuries of challenges demonstrates resilience that, combined with strategic adaptation, could secure a sustainable future. As the Kingdom in the Sky faces an uncertain horizon, its success will depend on transforming mountain barriers into bridges for development while maintaining the cultural foundations that enabled this remarkable nation's existence.