Guinea: West Africa's Water Tower

The Republic of Guinea, often called Guinea-Conakry to distinguish it from Guinea-Bissau and Equatorial Guinea, serves as West Africa's water tower, with major rivers including the Niger, Senegal, and Gambia originating in its highlands. This mineral-rich nation possesses the world's largest bauxite reserves and significant deposits of gold, diamonds, and iron ore. Despite these natural riches, Guinea remains one of the world's poorest countries, a paradox shaped by colonial exploitation, authoritarian rule, and governance challenges.

Geography: From Coast to Highlands

Guinea's diverse geography encompasses 245,857 square kilometers divided into four distinct natural regions, each with unique characteristics that have shaped settlement patterns, economic activities, and cultural development. From the Atlantic coast to the forest highlands, Guinea's landscape transitions through coastal plains, mountain ranges, savannas, and dense forests, creating one of West Africa's most ecologically diverse nations.

The Maritime Guinea (Basse-Guinée) region stretches along the Atlantic coast, characterized by mangrove swamps, estuaries, and coastal plains that rarely exceed 50 meters in elevation. This region receives the heaviest rainfall in the country, often exceeding 4,000 millimeters annually in some areas. The capital Conakry occupies a peninsula jutting into the Atlantic, while numerous rivers create a deltaic landscape supporting rice cultivation and fishing. Offshore, the Los Islands provide scenic beauty and historical significance as former slave trading posts.

The Fouta Djallon highlands dominate Middle Guinea, rising to over 1,500 meters and forming the watershed for West Africa's major rivers. These sandstone plateaus, deeply incised by valleys and waterfalls, create a landscape of dramatic beauty. The cooler climate and reliable water sources have made this region a center of Fulani civilization for centuries. Mount Loura, reaching 1,515 meters, stands as one of the highest peaks, while the sources of the Niger, Senegal, and Gambia rivers originate from these highlands, earning Guinea its nickname as the "water tower of West Africa."

Upper Guinea encompasses vast savanna plains that extend toward Mali and Côte d'Ivoire, characterized by seasonal grasslands dotted with baobab and shea trees. This region experiences a pronounced dry season and supports extensive cattle herding alongside cultivation of millet, maize, and groundnuts. The Forest Region (Guinée Forestière) in the southeast contains the last remnants of the Upper Guinean forests, including Mount Nimba, a UNESCO World Heritage site shared with Côte d'Ivoire and Liberia, harboring exceptional biodiversity including endemic species found nowhere else on Earth.

Total Area

245,857 km²

Population

13.5 million

Natural Regions

4 distinct zones

Highest Peak

Mount Nimba (1,752m)

Mineral Wealth: Blessing and Curse

Guinea sits atop one of the world's richest concentrations of minerals, particularly bauxite, the primary ore for aluminum production. The country possesses an estimated 25 billion tons of bauxite reserves, representing over one-third of global reserves. Major deposits in Boké, Fria, and Kindia have attracted international mining companies, making Guinea the world's second-largest bauxite producer after Australia. The distinctive red earth of bauxite mines dominates landscapes in mining regions.

Guinea's Mineral Resources

The country's geological wealth extends far beyond bauxite:

- Iron Ore - The Simandou mountains contain one of the world's largest untapped high-grade iron ore deposits, estimated at over 2 billion tons

- Gold - Significant deposits in the Upper Guinea region, with both industrial and artisanal mining operations

- Diamonds - Alluvial diamonds in the Forest Region, though production remains largely artisanal

- Uranium - Potential deposits identified but unexploited due to political and environmental concerns

- Nickel and Cobalt - Laterite deposits with potential for future development

Despite this mineral wealth, Guinea exemplifies the "resource curse" phenomenon. Mining contributes over 80% of export earnings but only about 20% of government revenues and employs less than 2% of the workforce. Weak governance, corruption, and unfavorable contracts have limited benefits for ordinary Guineans. Environmental degradation from mining, including deforestation, water pollution, and displacement of communities, creates additional costs borne primarily by rural populations.

Historical Foundations

Guinea's history reaches back to great West African empires. The Ghana Empire (8th-11th centuries) and later the Mali Empire (13th-16th centuries) incorporated parts of present-day Guinea, establishing trade routes and Islamic influence that persist today. The Fouta Djallon emerged as a major Islamic state in the 18th century when Fulani Muslims established a theocratic confederation that became a center of Islamic learning and political power in West Africa.

European contact intensified from the 15th century as Portuguese, then French and British traders established coastal posts. The slave trade devastated populations, with the Los Islands and Rio Pongo serving as major embarkation points. French colonial expansion accelerated in the late 19th century, meeting fierce resistance from leaders like Samori Touré, who fought French forces for nearly two decades before his capture in 1898. His grandson, Ahmed Sékou Touré, would later lead Guinea to independence.

French colonial rule imposed forced labor, taxation, and cash crop production while neglecting education and development. The colony of French Guinea became part of French West Africa, with Conakry serving as a regional administrative center. Colonial policies favored coastal elites while marginalizing interior populations, creating regional disparities that persist. The colonial economy focused on extracting raw materials, establishing patterns of dependency that would prove difficult to break.

Independence and Isolation

Guinea made history on September 28, 1958, when it became the first French African colony to reject membership in the French Community, choosing immediate independence under the leadership of Ahmed Sékou Touré. The vote was overwhelming: 95% chose independence despite French threats to withdraw all assistance. France's vindictive response included removing equipment, burning documents, and ending all aid overnight, leaving the new nation to build from scratch.

Sékou Touré's rule (1958-1984) began with pan-African idealism but devolved into paranoid authoritarianism. His Democratic Party of Guinea (PDG) established a one-party state promoting "African socialism" while suppressing opposition. The regime's human rights abuses included the notorious Camp Boiro prison where thousands of political prisoners were tortured and killed. Paranoia about plots led to purges that decimated the educated class, with an estimated 50,000 people killed and many more fleeing into exile.

Economic policies during this period proved disastrous. State control of the economy, collectivization attempts, and isolation from Western markets led to economic collapse. The introduction of the Guinean syli currency outside the franc zone further isolated the economy. By Sékou Touré's death in 1984, Guinea ranked among the world's poorest nations despite its natural wealth. The military coup that brought Lansana Conté to power promised liberalization but delivered another form of authoritarian rule that lasted until 2008.

Cultural Diversity

Guinea's population of approximately 13.5 million comprises over 24 ethnic groups, each maintaining distinct languages, customs, and social organizations. The Fulani (Peul) represent about 33% of the population, concentrated in the Fouta Djallon highlands where they established a sophisticated Islamic civilization. Their pastoral traditions, hierarchical social structure, and emphasis on Islamic education have profoundly influenced Guinean culture. The Fulani language (Pular) serves as a lingua franca in much of the interior.

Mandinka People

Comprising about 30% of the population, the Mandinka (Malinké) dominate Upper Guinea's savanna regions. Descendants of the Mali Empire, they maintain strong oral traditions through griots who preserve history, genealogies, and cultural values through music and storytelling. Their society emphasizes age grades and initiation ceremonies.

Susu People

The Susu (20%) concentrate in coastal regions, historically serving as intermediaries in trade. Their culture blends Islamic practices with traditional beliefs, including powerful secret societies. Susu traders played crucial roles in regional commerce, and their language remains important in coastal areas and Conakry.

Forest Peoples

The Forest Region hosts diverse groups including Kissi, Toma, and Guerze peoples. These communities maintain animist traditions alongside Christianity and Islam, with masked dances and forest spirits playing important cultural roles. Their knowledge of forest resources includes sophisticated agricultural and medicinal practices.

Islam dominates religious life, practiced by approximately 85% of Guineans, though often blended with traditional beliefs. Christianity (8%) concentrates in urban areas and the Forest Region, while traditional religions persist, particularly in rural areas. Religious tolerance generally prevails, with interfaith marriages common and religious holidays celebrated across communities. Traditional practices like initiation ceremonies, ancestor veneration, and healing rituals continue alongside organized religions.

Regional Profiles

Conakry: Overcrowded Capital

Originally built for 50,000 inhabitants, Conakry now houses over 2 million people – nearly 20% of Guinea's population. The city sprawls along the Kaloum Peninsula and mainland suburbs, with inadequate infrastructure struggling to serve explosive growth. Colonial-era buildings in the city center contrast with sprawling informal settlements. The port handles most international trade, while markets like Madina provide vibrant commercial activity. Chronic electricity and water shortages, traffic congestion, and waste management challenges plague daily life.

Fouta Djallon: Highland Heart

This highland region centers on cities like Labé and Dalaba, maintaining distinct Fulani cultural identity. The cool climate supports dairy farming and fruit cultivation, including oranges that thrive in the highlands. Traditional architecture features round huts with conical thatched roofs adapted to heavy rainfall. Islamic scholarship flourishes in numerous Quranic schools. Tourism potential exists in waterfalls, hiking trails, and cultural experiences, though infrastructure remains limited. The region's conservative social structure contrasts with coastal areas.

Contemporary Challenges

Guinea's transition to democracy remains incomplete despite progress since 2010. The first democratic election brought Alpha Condé to power, raising hopes for change. However, his controversial third term in 2020, achieved through constitutional manipulation, sparked violent protests. The September 2021 military coup led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya reflected widespread frustration with corruption and democratic backsliding. The junta promises a transition to civilian rule, but timelines remain uncertain.

Economic challenges persist despite mineral wealth. Over 55% of Guineans live below the poverty line, with rural areas particularly disadvantaged. Youth unemployment exceeds 60%, driving urban migration and social tensions. Infrastructure deficits include inadequate electricity (less than 35% access), poor roads, and limited healthcare facilities. The education system struggles with overcrowded classrooms, undertrained teachers, and low completion rates, particularly for girls.

Corruption permeates all levels of society, from petty bribes to grand theft of mining revenues. Weak institutions, politicized justice systems, and lack of accountability enable systematic corruption. Environmental degradation accelerates through uncontrolled mining, deforestation for charcoal and agriculture, and urban expansion. Climate change brings irregular rainfall patterns, threatening agricultural livelihoods. Regional instability, including conflicts in neighboring countries, creates refugee flows and security concerns.

Economic Sectors

Agriculture employs about 75% of the workforce but contributes only 20% to GDP, highlighting low productivity. Subsistence farming dominates, with rice as the staple crop supplemented by cassava, maize, and groundnuts. Cash crops include coffee, cocoa, palm oil, and fruits, though poor infrastructure limits market access. The livestock sector, particularly important in the Fouta Djallon, faces challenges from disease and limited veterinary services.

The service sector, concentrated in Conakry, includes telecommunications, banking, and informal trade. Mobile phone penetration exceeds 100%, enabling mobile banking and improving rural connectivity. The informal sector dominates urban employment, with petty trade, transportation, and services providing survival livelihoods. Tourism remains underdeveloped despite significant potential in ecotourism, cultural tourism, and adventure travel.

Manufacturing remains minimal, limited to beverage production, food processing, and construction materials. The lack of reliable electricity, skilled workers, and supporting infrastructure constrains industrial development. Artisanal production includes textiles, leather goods, and crafts, though mostly for local consumption. Value addition to raw materials remains a missed opportunity, with bauxite exported unprocessed and agricultural products sold fresh rather than processed.

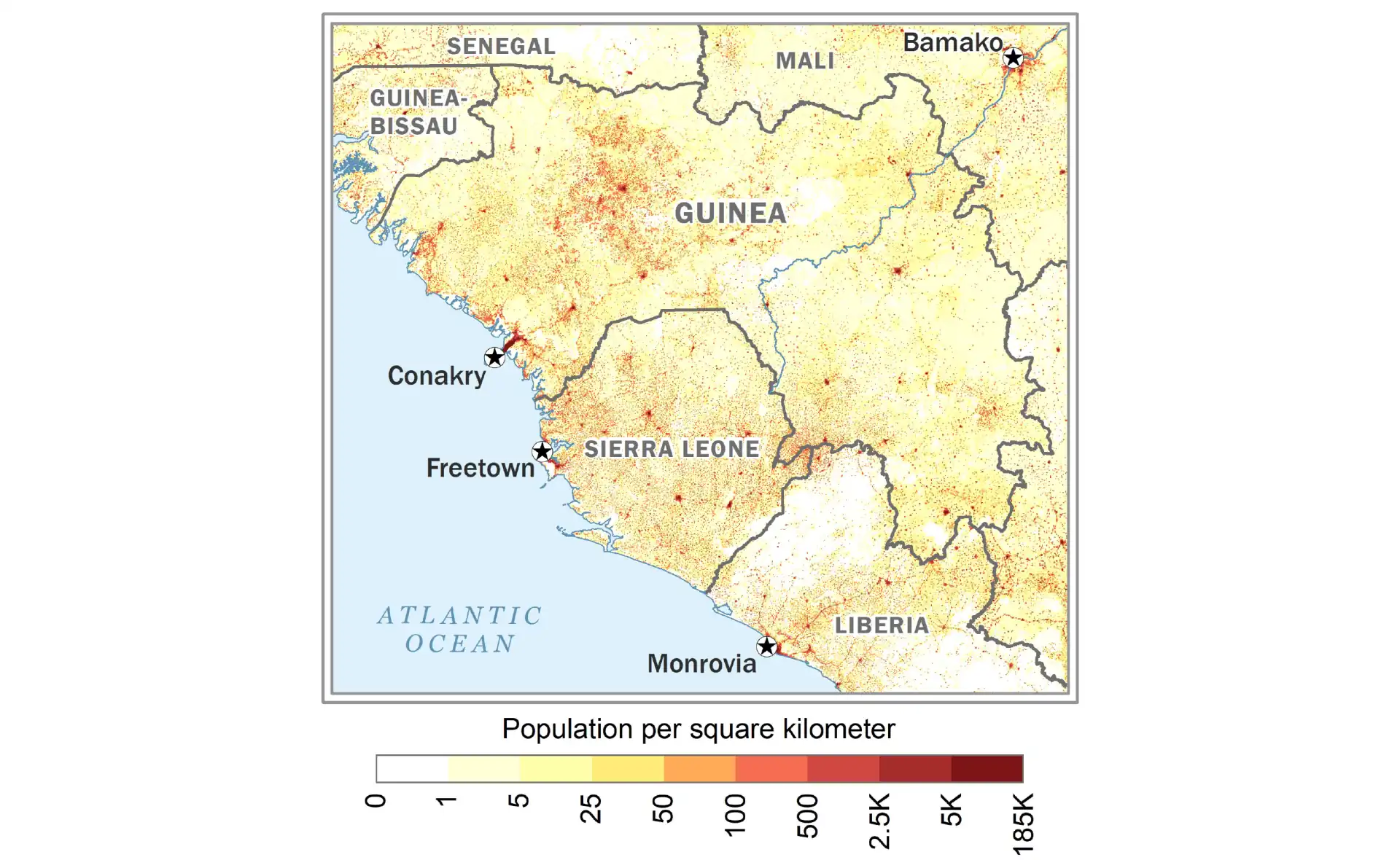

Population Distribution and Density

Guinea's population of approximately 13.5 million is distributed unevenly across its four natural regions, with density patterns reflecting geographic constraints, economic opportunities, and historical settlement patterns. The coastal region around Conakry hosts the highest density (over 300 people per square kilometer), while vast areas of the interior highlands and savannas maintain much lower densities.

The Fouta Djallon highlands show moderate population density (50-150 people per square kilometer) concentrated in valleys and around towns like Labé and Mamou, where the cooler climate and water availability support settled agriculture. Upper Guinea's savannas have lower density (20-50 people per square kilometer) with populations clustered around market towns and along rivers. The Forest Region shows varied density - high around N'zérékoré and other towns but very low in protected forest areas. Rural-to-urban migration continues to concentrate population in Conakry, which now holds nearly 20% of the national population despite infrastructure constraints.

International Relations

Guinea maintains complex relationships with neighboring states, balancing regional cooperation with sovereignty concerns. The Mano River Union, including Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Côte d'Ivoire, promotes economic integration despite historical conflicts. Border disputes occasionally flare, particularly in resource-rich areas. Guinea hosts refugees from regional conflicts while its own citizens migrate for economic opportunities. ECOWAS membership provides frameworks for cooperation, though Guinea faced suspension following the 2021 coup.

China has emerged as a major partner, investing billions in infrastructure projects in exchange for mining concessions. The relationship includes the construction of roads, dams, and government buildings, though concerns about debt sustainability and labor practices persist. Traditional partners like France maintain economic interests despite political tensions. Russia seeks expanded influence through military cooperation and mining investments. The United States provides development assistance while pressing for democratic reforms.

International mining companies dominate the extractive sector, with complex relationships involving revenue sharing, environmental responsibilities, and community relations. Companies from Australia, China, Russia, and other nations compete for concessions, sometimes fueling corruption. International financial institutions provide loans and grants tied to governance reforms, with mixed results. The diaspora, particularly in France and the United States, provides remittances and maintains political engagement.

Future Prospects

Guinea's future hinges on breaking the resource curse through better governance and economic diversification. The Simandou iron ore project, if developed transparently, could transform the economy but requires massive infrastructure investment and careful management. Agricultural modernization could improve food security and create employment if supported by infrastructure development and market access. The country's water resources offer hydroelectric potential to address energy deficits.

Democratic consolidation remains crucial for stability and development. The current transition presents opportunities for institutional reforms, though military interference risks persist. Youth engagement in politics and civil society offers hope for change, but requires space for participation and economic opportunities. Regional integration could expand markets and promote stability if political will exists. Education reform, particularly in technical and vocational training, could address skills gaps.

Ultimately, Guinea's vast natural wealth could support broad-based development if managed transparently and sustainably. The young population, with median age around 19, represents both a challenge requiring job creation and an opportunity for transformation. Success requires breaking cycles of authoritarian rule, corruption, and resource exploitation that have impoverished a naturally wealthy nation. Whether Guinea can finally translate its position as West Africa's water tower and mineral giant into prosperity for its people remains the central question for this pivotal African nation.