Guinea-Bissau: Land of a Thousand Islands

The Republic of Guinea-Bissau encompasses one of West Africa's most remarkable geographic features: the Bijagós Archipelago with its 88 islands scattered across the Atlantic. This small nation, roughly the size of Switzerland, gained independence from Portugal in 1974 after a protracted liberation war. Despite chronic political instability and economic challenges, Guinea-Bissau maintains extraordinary biodiversity in its mangrove forests, coastal wetlands, and marine ecosystems, while its diverse ethnic groups preserve unique cultural traditions in one of Africa's least-visited countries.

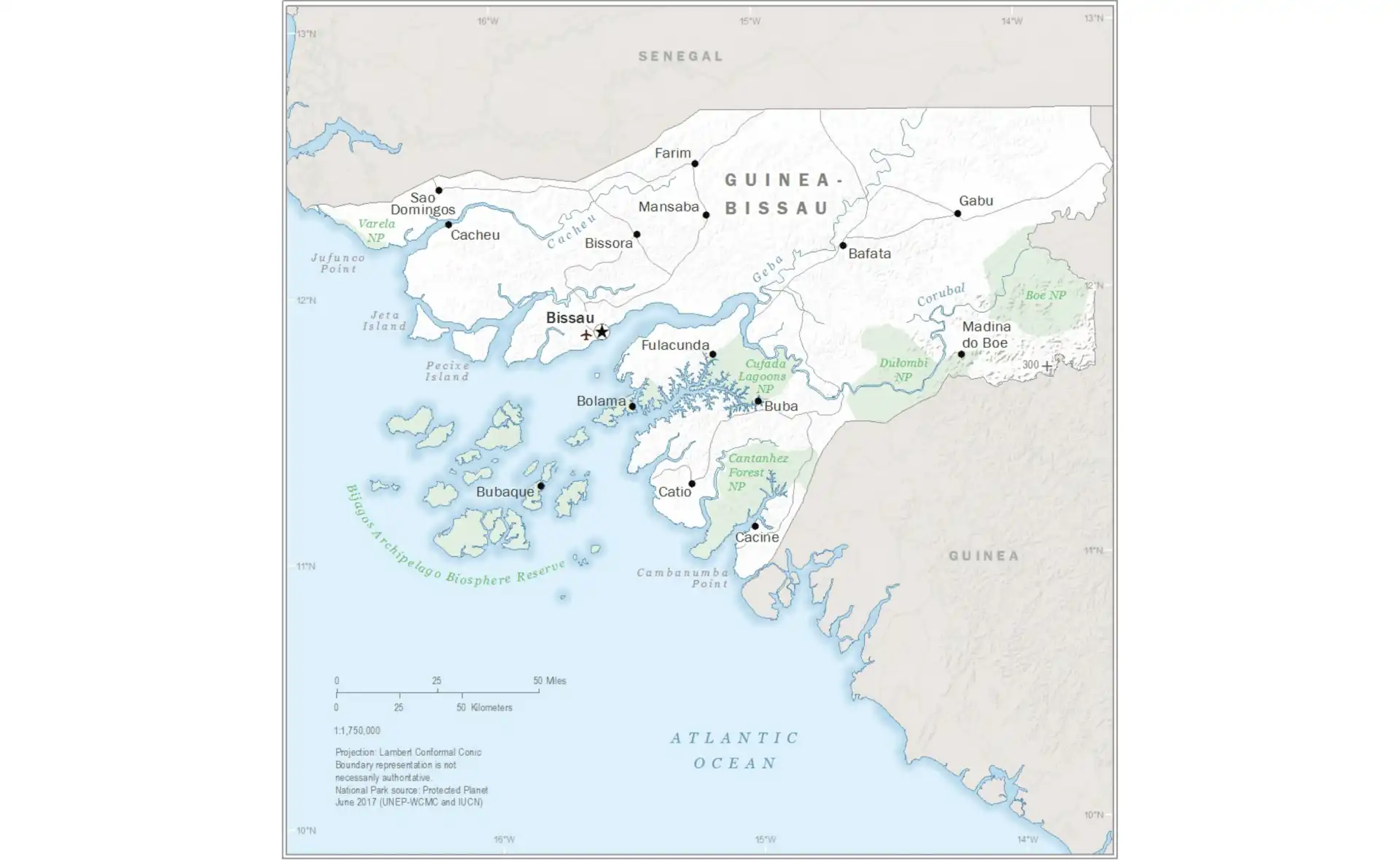

Geographic Diversity: From Islands to Interior

Guinea-Bissau covers 36,125 square kilometers, with about one-fifth consisting of water, tidal flats, and mangrove swamps. The mainland divides into coastal lowlands and slightly elevated interior plateaus, with the highest point reaching only 300 meters. This low-lying topography creates extensive wetlands during the rainy season, transforming the landscape into a maze of waterways and flooded plains. The Corubal and Geba rivers, along with their tributaries, form dendritic patterns across the country, creating fertile alluvial soils but also challenging transportation networks.

The Bijagós Archipelago represents Guinea-Bissau's crown jewel, stretching across 100 kilometers of ocean with 88 islands, of which only 23 are inhabited year-round. These islands formed from ancient river deltas now submerged by rising sea levels, creating unique ecosystems where forest meets ocean. Orango, the largest island, covers 272 square kilometers and hosts the country's only national park. The archipelago's isolation preserved both biodiversity and traditional culture, with some islands remaining sacred spaces where modern development is restricted by indigenous customs.

Mangrove forests cover approximately 8% of the national territory, forming one of West Africa's most extensive mangrove systems. These tidal forests line rivers and coasts, creating nurseries for fish, habitat for manatees, and protection against coastal erosion. The mangroves' twisted roots rise above high tide levels, creating otherworldly landscapes that change dramatically with tidal cycles. Beyond the coastal zone, the interior transitions to woodland savanna dominated by palm trees, baobabs, and seasonal grasslands that support both wildlife and traditional agricultural systems.

Total Area

36,125 km²

Islands

88 islands

Population

2.0 million

Coastline

350 km

The Bijagós Archipelago: A World Apart

The Bijagós Archipelago maintains one of West Africa's most intact traditional societies, where matriarchal structures and animist beliefs shape daily life. The Bijagó people, numbering about 30,000, have inhabited these islands for centuries, developing sustainable practices that balance human needs with environmental preservation. Women hold significant power in Bijagó society, choosing husbands and managing household economies, while men focus on fishing and palm wine production. This gender dynamic, rare in West Africa, reflects adaptation to island life where women's knowledge of agriculture and resource management proved essential.

Island Ecosystems and Culture

The Bijagós Islands harbor remarkable biodiversity and cultural practices:

- Sacred Forests - Protected groves where ancestors' spirits reside, maintaining biodiversity through traditional taboos

- Marine Megafauna - Sea turtles nest on beaches, hippos swim between islands, and manatees graze in shallow waters

- Traditional Architecture - Circular mud houses with conical thatched roofs adapted to tropical storms

- Initiation Ceremonies - Young men spend months in sacred forests learning cultural knowledge and survival skills

- Sustainable Fishing - Traditional techniques using tides and seasonal migrations preserve fish stocks

Island isolation created unique ecological conditions where saltwater hippos evolved smaller size to swim between islands, representing one of only a few marine hippo populations worldwide. Green sea turtles nest on pristine beaches from July to November, with some beaches hosting thousands of nests. The islands' forests shelter rare primates, including Campbell's monkeys and western chimpanzees, while mudflats support millions of migratory birds traveling between Europe and Africa. This biodiversity attracts researchers and eco-tourists, though visitor numbers remain minimal due to limited infrastructure.

Historical Layers

Before European contact, the region housed various ethnic groups organized in decentralized societies practicing agriculture, fishing, and trade. The great Mali Empire extended influence into parts of present-day Guinea-Bissau during the 13th-14th centuries, introducing Islam to some communities. However, most groups maintained animist beliefs and local governance structures. Coastal peoples developed sophisticated rice cultivation in tidal zones, creating a unique agricultural system that persists today. Trade networks connected the interior with trans-Saharan routes while coastal communities engaged in regional maritime commerce.

Portuguese exploration began in 1446 when Nuno Tristão sailed along the coast, but meaningful colonization didn't occur until the late 19th century. Portugal established trading posts primarily for the slave trade, with Cacheu and Bissau serving as major ports. Unlike other Portuguese colonies, Guinea-Bissau never developed plantation agriculture or significant European settlement. The colony served mainly as a source of slaves for Cape Verde and the Americas, creating lasting demographic and social impacts. Portuguese control remained limited to coastal areas and a few interior posts, with most territories maintaining effective independence.

The liberation war from 1963-1974, led by Amílcar Cabral and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), became one of Africa's most successful guerrilla campaigns. PAIGC controlled over two-thirds of the territory by 1973, establishing schools, healthcare, and governance in liberated zones. Cabral's assassination in January 1973 didn't derail independence, achieved on September 24, 1973—making Guinea-Bissau the first Portuguese African colony to gain independence. The struggle's legacy shapes national identity, though post-independence unity proved elusive.

Ethnic Diversity and Languages

Guinea-Bissau's approximately 2 million inhabitants comprise over 20 ethnic groups, each maintaining distinct languages and customs. The Balanta, the largest group at about 30%, traditionally practice animism and occupy the southern coastal regions where they cultivate rice in intricate paddy systems. Known for their egalitarian society without centralized chiefs, the Balanta played crucial roles in the independence struggle. The Fula (20%) and Mandinka (14%) in the interior practice Islam and maintain hierarchical societies with traditional rulers. These groups historically engaged in trade and cattle herding, creating cultural corridors linking Guinea-Bissau with the broader West African Islamic world.

Linguistic Landscape

While Portuguese serves as the official language, only about 11% speak it fluently. Guinea-Bissau Creole (Kriol), blending Portuguese with African languages, functions as the lingua franca spoken by 90% of the population. Each ethnic group maintains its language, creating a multilingual society where individuals commonly speak three or four languages. This linguistic diversity reflects historical trade patterns and cultural resilience.

Religious Syncretism

Traditional African religions remain strong with about 45% adherence, while Islam (45%) and Christianity (10%) show syncretic practices. Many Muslims and Christians incorporate ancestral veneration and traditional healing. Sacred forests, spirit mediums, and traditional ceremonies coexist with mosques and churches. This religious fluidity allows multiple spiritual practices without conflict.

Social Organization

Age groups and secret societies organize social life across ethnic lines. Initiation ceremonies mark transitions to adulthood, teaching cultural values and practical skills. Women's associations wield significant influence in agriculture and trade. Extended families provide social security, with complex reciprocal obligations ensuring community support during hardships.

Cultural expressions include vibrant music traditions blending African rhythms with Portuguese influences. Gumbe, the national music genre, evolved from colonial-era interactions, featuring polyrhythmic drumming and call-and-response vocals. Traditional instruments like the balafon (wooden xylophone) and kora (harp-lute) accompany ceremonies and storytelling. Carnival celebrations in Bissau showcase cultural fusion with elaborate masks and costumes drawing from various ethnic traditions. These artistic expressions maintain cultural identity while adapting to urban contexts.

The Cashew Economy

Cashew nuts dominate Guinea-Bissau's economy, accounting for over 90% of exports and providing income for approximately two-thirds of households. Introduced by Portuguese colonizers in the 1950s, cashew trees thrived in the tropical climate and poor soils where other crops struggled. The trees require minimal maintenance, making them ideal for smallholder farmers. During harvest season from March to June, entire families participate in collecting nuts, creating a cash economy in otherwise subsistence-oriented rural areas.

Cashew Production Challenges

Despite being the world's fifth-largest cashew producer, Guinea-Bissau faces significant challenges:

- Lack of Processing - Over 95% of cashews export raw to India and Vietnam for processing, losing value-added opportunities

- Price Volatility - International market fluctuations devastate farmer incomes with no alternative crops

- Aging Trees - Many orchards exceed optimal productivity age with limited replanting

- Transportation - Poor roads and infrastructure increase costs and post-harvest losses

- Quality Control - Lack of standards and storage facilities reduces premium market access

Recent initiatives promote cashew processing within Guinea-Bissau to capture more value, though progress remains slow due to capital constraints and technical challenges. Small-scale processing units employ mainly women, providing off-farm income. The government attempts to regulate farmgate prices to protect farmers, with mixed success. Organic certification programs tap into premium markets, though certification costs limit participation. Economic diversification beyond cashews remains critical but elusive, with rice production declining and few alternative cash crops suited to local conditions.

Political Instability and Governance

Since independence, Guinea-Bissau has experienced chronic political instability with multiple coups, attempted coups, and constitutional crises. No elected president has completed a full term in office, creating a cycle of instability that hampers development. The military repeatedly intervenes in politics, often citing corruption or constitutional violations. This instability stems partly from weak institutions inherited from minimal colonial development and competition for control over limited state resources. Drug trafficking through the country, earning it the label "narco-state," further corrupts politics.

The 1998-1999 civil war devastated infrastructure and displaced hundreds of thousands, setting back development significantly. Subsequent years saw a revolving door of presidents and prime ministers, with the military arbitrating political disputes. The 2012 coup interrupted a promising democratic transition, leading to international sanctions. Recent elections show tentative progress toward stability, though political tensions remain high. Ethnic and regional divisions overlay political competition, with parties often representing specific ethnic constituencies rather than ideological positions.

Weak state capacity limits service delivery outside the capital. Most rural areas lack electricity, paved roads, and basic healthcare. Teachers and healthcare workers often go unpaid for months, disrupting already minimal services. Traditional authorities fill governance gaps in rural areas, resolving disputes and managing resources through customary law. This parallel governance system sometimes conflicts with state authority but provides essential services where the state fails. International interventions, including ECOWAS peacekeeping missions, temporarily stabilize situations without addressing underlying problems.

Biodiversity and Conservation

Guinea-Bissau's wetlands and forests support exceptional biodiversity, including several globally threatened species. The coastal waters host West African manatees, Atlantic humpback dolphins, and five species of sea turtles. Terrestrial fauna includes forest elephants, though populations declined drastically from hunting. Chimpanzees survive in fragmented forest patches, while the archipelago's unique fauna includes tool-using chimps that crack open oysters. Over 470 bird species make the country a birding paradise, with massive congregations of Palearctic migrants in coastal mudflats.

Conservation efforts face severe challenges from poverty, weak governance, and limited resources. The Orango National Park, established in 2000, protects critical marine and terrestrial habitats but struggles with inadequate funding and staff. Community-based conservation shows promise, particularly where traditional practices align with conservation goals. The Bijagós Biosphere Reserve, recognized by UNESCO, attempts to balance conservation with sustainable development. However, illegal fishing by foreign vessels, uncontrolled hunting, and habitat conversion for cashew plantations threaten biodiversity.

Climate change impacts manifest through coastal erosion, changing rainfall patterns, and rising sea levels that threaten low-lying areas. Mangrove cutting for rice cultivation and fuelwood accelerates coastal vulnerability. Recent conservation initiatives focus on mangrove restoration and sustainable fishing practices. International NGOs support community conservation projects, though coordination remains weak. The country's biodiversity represents both an irreplaceable natural heritage and potential eco-tourism resource, if political stability allows development of sustainable tourism infrastructure.

Urban Life in Bissau

Bissau, the capital and largest city with about 400,000 inhabitants, reflects the country's challenges and modest progress. The city center retains Portuguese colonial architecture, though many buildings show severe deterioration. The Fortaleza de São José da Amura, now housing a military museum, overlooks the port where rusty vessels hint at better times. Modern Bissau spreads chaotically beyond the colonial core, with informal settlements housing most residents. Markets burst with activity, particularly Bandim Market where everything from cashews to traditional medicines trades hands.

Infrastructure in Bissau remains precarious. Electricity supply is erratic, with most relying on generators when available. Water systems function sporadically, forcing residents to depend on wells and water vendors. Roads, particularly during the rainy season, become nearly impassable in many neighborhoods. Despite challenges, Bissau shows vibrant cultural life. Music venues feature live gumbe performances, while restaurants serve fresh seafood and traditional dishes. The annual Carnival rivals any in Lusophone Africa, temporarily transforming the city into a celebration of cultural diversity.

Youth dominate Bissau's demographics, with limited opportunities creating frustration and driving irregular migration to Europe. Internet cafes and mobile phones connect youth to global culture, creating aspirations difficult to fulfill locally. Universities struggle with limited resources, though students actively engage in political and cultural movements. The informal economy provides most employment, from street vending to motorcycle taxis. NGOs and international organizations maintain significant presence, providing services and employment but also creating parallel structures that sometimes undermine state capacity.

Food Security and Agriculture

Despite fertile soils and adequate rainfall, Guinea-Bissau faces food insecurity with rice imports necessary to feed the population. Traditional rice cultivation in mangrove areas (bolanha) produces high-quality rice but requires intensive labor for dyke construction and maintenance. Younger generations increasingly abandon this backbreaking work for cashew cultivation or urban migration. Upland rice cultivation expanded but yields remain low without fertilizers or improved varieties. The shift from food crops to cashews creates vulnerability when cashew prices fall or harvests fail.

Fishing provides crucial protein and income for coastal communities. Artisanal fishers using pirogues catch diverse species for local consumption and regional trade. However, industrial fishing vessels from Europe and Asia deplete fish stocks, often operating illegally in Guinea-Bissau waters. Weak maritime surveillance allows this pillaging of marine resources, depriving local fishers of livelihoods. Recent agreements with the EU provide some revenue but inadequately compensate for resource depletion. Aquaculture potential remains unexplored despite suitable conditions.

Food systems show resilience through indigenous knowledge and crop diversity. Women cultivate vegetable gardens using traditional irrigation. Wild foods from forests and mangroves supplement diets during lean seasons. Palm wine production provides income and cultural continuity. Traditional food preservation techniques adapt to lack of refrigeration. However, changing climate patterns, particularly irregular rainfall, challenge traditional agricultural calendars. Promoting agricultural diversification while supporting traditional sustainable practices could enhance food security, but requires investment and stability lacking in current conditions.

Health and Social Services

Healthcare in Guinea-Bissau ranks among the world's weakest, with one doctor per 5,000 people and most medical professionals concentrated in Bissau. Rural health posts often lack basic supplies and trained staff. Maternal mortality remains extremely high due to limited access to emergency obstetric care. Malaria accounts for the largest disease burden, while tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS present growing challenges. Traditional medicine fills healthcare gaps, with healers providing culturally appropriate care though sometimes delaying critical medical treatment.

Education faces similar challenges with low enrollment and completion rates, particularly for girls. Schools often lack basic materials, qualified teachers, and infrastructure. Teachers frequently strike over unpaid salaries, disrupting academic calendars. Rural schools might have one teacher for multiple grades in deteriorating buildings. Despite challenges, literacy campaigns and community schools show progress. Koranic schools provide alternative education, though quality varies widely. Higher education remains limited with one public university struggling to maintain standards.

Social protection systems barely exist beyond traditional family support networks. Extended families care for orphans, elderly, and disabled members, though urbanization strains these systems. Women's groups provide rotating credit and social support. International NGOs fill some gaps but create dependency without building local capacity. Youth face particular challenges with few opportunities for education, employment, or civic engagement. Sports, particularly football, provide rare opportunities for achievement and potential escape from poverty. Building effective social services requires political stability and resources currently devoted to political competition.

Future Prospects

Guinea-Bissau's future depends on breaking cycles of political instability and economic dependence. The young population, with over 60% under 25, could drive transformation if provided opportunities. Untapped resources including offshore oil, mineral deposits, and tourism potential offer development possibilities. The strategic location for maritime trade and fishing could generate revenue if properly managed. Renewable energy potential from solar and tidal power could address energy deficits. However, realizing potential requires governance improvements seemingly beyond current capacity.

Regional integration through ECOWAS provides frameworks for stability and development, though implementation lags. The African Continental Free Trade Area might open markets for processed cashews and other products. Climate finance could support adaptation and conservation efforts. Diaspora remittances and knowledge transfer offer resources for development. Technology adoption, particularly mobile banking and communications, shows rapid progress despite infrastructure limitations. Young entrepreneurs demonstrate innovation when given minimal support.

Conservation of unique biodiversity could attract eco-tourism and research investments if security improves. Sustainable management of marine resources could ensure long-term food security and livelihoods. Cultural tourism potential exists in the Bijagós Islands and historical sites. However, these opportunities require stability, infrastructure, and governance improvements. Without addressing political dysfunction and building inclusive institutions, Guinea-Bissau risks remaining trapped in poverty despite abundant natural and human resources. The challenge lies not in identifying solutions but in creating conditions for their implementation. As one of the world's least developed countries, Guinea-Bissau's path forward requires both internal transformation and sustained international support focused on building local capacity rather than perpetual emergency assistance.